You’ve probably seen the news about how a certain celebrity can’t a get a trademark for apparel bearing the despicable phrase, “White Lives Matter.”

Let’s breakdown what’s happened in this situation so far:

- Everyone justifiably lost their minds when a celebrity wore a shirt that said “White Lives Matter” in a fashion show in Paris this fall.

- The news reported that, even if this celebrity wanted to register a trademark for “White Lives Matter” for apparel in the U.S., he can’t because someone else already filed that trademark application with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) on October 3, 2022.

- The applicant for this trademark subsequently assigned this trademark to Civic Cipher, LLC, a syndicated black radio show on October 17, 2022.

How ITU Trademark Applications Work

The trademark application in question is only an Intent To Use (ITU) application. A company or person can file an ITU application when they expect to bring a good or service to market within 6 months, and it’s a way to stake a claim in the desired trademark, so no one else takes it in the meantime.

Once the USPTO issues a Notice of Acceptance for your ITU application, you have 6 months to either submit a Statement of Use, proving that you’re using the trademark in commerce, or you can request a 6-month extension. The USPTO will grant you up to 5 extensions, so essentially, you actually have up to 3 years to bring your product or service to market. If you don’t do it by then, that trademark application is “dead,” and you have to file a new trademark application and start over.

The upside of filing an ITU application is that your federal rights date back to when you filed the application with the USPTO.

That means Civic Cipher, a black radio show, will have to sell White Lives Matter branded apparel to get the registered trademark.

Black Radio Show is Selling WLM Shirts (allegedly)

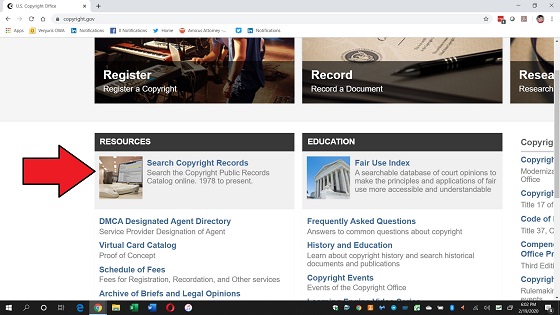

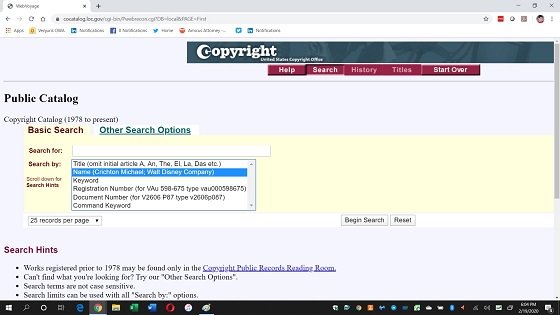

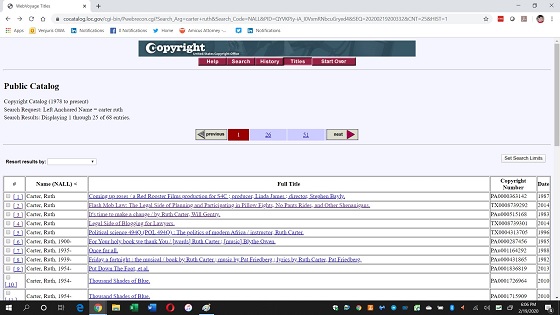

As I was working on this post, I popped over to the USPTO trademark database (publicly available and free), to look up this trademark application. To my surprise, Civic Cipher submitted proof that they’re selling White Lives Matter branded apparel on November 8, 2022. Here’s the picture of their proof.

Civic Cipher did something very smart. They didn’t just take and submit a picture of a White Lives Matter t-shirt. This shirt has a tag that says, “White Lives Matter.” That’s the real branding and proof that they’re using the trademark.

Here’s something important to know if you have or want to sell a brand of apparel:

Phrases on T-shirts Aren’t Trademarks

That’s right – putting a word, phrase, or logo on a shirt does not make it a trademark for apparel. The shirt is the product. The trademark is the branding on it, like on the tag inside the shirt, the paper tag attached to it at the store, and/or the bag or box it’s delivered in. That’s where the trademark for the product goes. The trademark goes on the product; it’s not the product itself.

The purpose of a trademark is to prevent consumer confusion. They don’t want Company B to copy Company A’s branding so closely that consumers might buy Company B’s product, thinking it’s from Company A.

Even though a phrase on a shirt isn’t a trademark, there’s still an argument that Civic Cipher could send cease and desist letters or takedown notices to prevent others from selling White Lives Matter t-shirts, asserting as the trademark owner, they have exclusive control over who sells apparel containing their brand in the U.S. – if the USPTO registers their trademark.

Civic Cipher Doesn’t Have a Registered Trademark Yet

The trademark application for White Lives Matter for apparel was filed on October 3, 2022. The USPTO’s backlog is so massive, it takes them more than 8 months to do the initial review of a new trademark application.

That means the USPTO won’t weigh in on whether White Lives Matter is trademarkable until May 2023 at the earliest.

Even if Civic Cipher did everything correct with their trademark application, the USPTO could refuse to register it on grounds that it contains “immoral, deceptive, or scandalous matter.”

This is a gray area of the law. It’s ok to have a disparaging trademark (e.g., “The Slants” as a trademark for an Asian music group) and to use swear words in your trademarks; however, the Ku Klux Klan can’t register their organization’s name as trademark. I don’t know how the examining attorney assigned to this application will classify “White Lives Matter.”

(Yes, whether your trademark complies with U.S. Trademark Law is determined by an individual, and different examining attorneys have come to different conclusions regarding the same trademark application.)

Where is Civic Cipher Selling their WLM Apparel?

One of the rules to get a trademark is, to be “in commerce,” you have to have a bona fide offer of sale to the public. You don’t have to make a sale, but your product or service has to be available to the public.

For most of my clients, this means they have to have a website where they show or describe the product, with a price, and button that allows consumers to make a purchase.

Since Civic Cipher has submitted proof that they’re using their mark “in commerce,” I wanted to see where it’s available for sale. Civic Cipher has a Redbubble online store where they sell Civic Cipher t-shirts, but the White Lives Matter shirt isn’t listed there.

When a simple Google search didn’t yield any useful results, I contacted Civic Cipher directly. (I haven’t heard back yet.) I would not be surprised if the price on this shirt is outrageously high or if all the profits go to a charity that helps black people.

Did You Like This? Subscribe for More!

If you liked this post and want more, please subscribe to Ruth & Consequences. This fortnightly newsletter gives you exclusive content and a behind-the-scenes look into my life as a non-binary lawyer and entrepreneur and the lessons I learn as the Evil Genius behind Geek Law Firm. (When you own the business, you get to pick your own title.)